Research suggests public service advice no longer 'free and frank'

Dr Chris Eichbaum surveyed the ‘freeness and frankness’ of advice given by New Zealand’s increasingly politicised public service in 2005 and 2017.

Reader in Government at Victoria Business School Dr Chris Eichbaum, and Professor Richard Shaw from Massey University, have found officials becoming more guarded in and around an increasingly politicised Beehive. In this opinion piece, they suggest a few remedies for the new Government to consider.

The duo carried out survey research in 2005 with public servants, Ministers (past and present) and political staff (past and present) – and earlier this year surveyed mainly public servants, retired public servants, and others with a direct involvement or interest in public administration. In 2017 there were 640 of these respondents.

Professor Shaw was also interviewed on National Radio about their survey findings, with a link to the audio below.

The 'official Wellington bureaucratic narrative'

"Let’s get one thing clear. We are as free and frank now as we have ever been. Everyone tells me so. It’s part of the brand."

No one has said this in these terms, but this construct is an accurate reflection of what might be described as the 'official Wellington bureaucratic narrative'. And you can find elements in speeches emanating from central agencies, blog posts and the like.

The problem is that – and we can say this with some confidence – that's not the view of the women and men in the engine room of public administration in New Zealand. What they tell us is that things have changed, and not for the better.

They tell us that too many Ministers no longer want free and frank advice and they tell us that Ministerial staff interject themselves into administrative processes to filter out advice that a Minister may need to hear but that she or he (or their dutiful adviser) deems unhelpful, or potentially embarrassing if – heaven forbid – it should ever make its way onto the front page of The Dominion Post (or more generally the public domain). They tell us that political advisers patrol the perimeters of the Ministerial office managing who gets to see the Minister, and who stays beyond ‘the wire’.

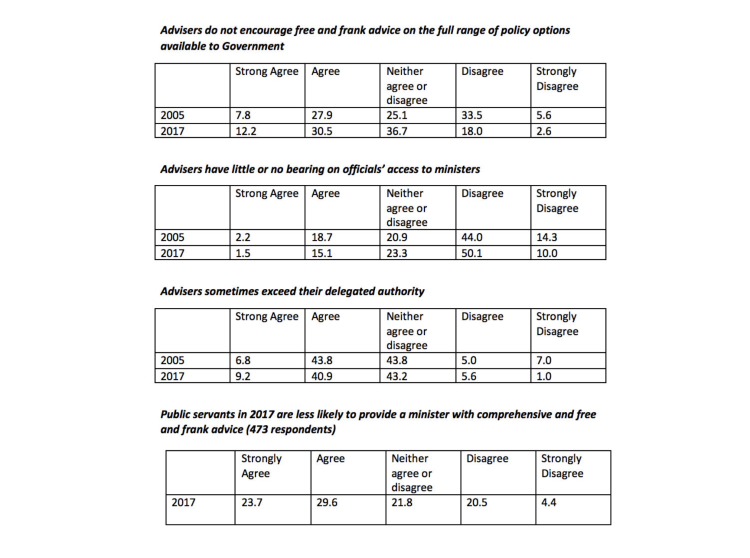

We carried out survey research in 2005 and earlier this year. In 2005 we surveyed public servants, Ministers (past and present) and political staff (past and present) – this year our respondents were mainly public servants, retired public servants, and others with a direct involvement or interest in public administration. This year there were 640 of these respondents.

Change arrives in the mid-1980s

A word or two about the past (with apologies to those who might have an allergic response to any notion of a golden age).

In a Ministers office we find a Minister and her or his staff. Up until the early to mid-1980s those staff were public servants of the non-political kind. The Office was ‘headed up’ by a Senior Private Secretary (allocated to the Minister from a pool employed by the Department of Internal Affairs).

These were 'serial loyalists' and stayed with the office. When the government changed, they stayed, and so a new Minister would inherit someone who 'knew the ropes', which included knowing the heads of government departments, and key people in the Beehive and without.

There was a time when Press Secretaries too were allocated from a pool employed by the Department of Tourism and Publicity. They too knew 'the ropes' – they had relationships with the Press Gallery, and they were practised at the craft of drafting press statements and speeches.

This is not to suggest that Ministers did not have other sources of advice, including political advice. They had their Ministerial and Caucus colleagues, their Party members, and their partners – there was no shortage of advice whether that was provided across the farm fence or at a branch meeting of a trade union. Indeed, up until the mid-1980s such advice was seen as a virtuous element of New Zealand pluralist politics.

That was before we deemed interests to be vested, and what was formerly virtuous to be somewhat venal, so what changed was that advice became institutionalised. In the Ministers Office these days, most staff are political appointees. Senior Private Secretaries are individuals known to, loyal to, and selected by the Minister and, leaving aside the potential for a loss of institutional knowledge and the time taken to 'learn the ropes', there is nothing wrong in that.

So too with the press secretaries and the political advisers – these will be, for the most part, true believers, whether the faith is support for a preferred policy, personal loyalty to the person of the Minister or the Prime Minister (or perhaps a Chief of Staff) or a shared commitment to the philosophy of a political party (and even membership of that party).

The only 'non-political' staff in most offices these days are the Private Secretaries seconded from departments or agencies within the Minister’s portfolio – and it is an open question as to how active they are in terms of 'policy conversations' in the office. Anecdotally we hear that they have become administrative conduits in a chain, adept at navigating (or constructing) pathways between the political and the administrative worlds (referred to by some, as a 'purple zone').

Of course, the world has changed in other ways as well, and the Ministerial office has changed as a result. We have entered a world where political communications are pre-emptive and proactive. Some say we live in a time of the continuous campaign, where the cliched comment of the party leader on election night to the effect that ‘the campaign for the next election starts now’ is no longer a cliché.

Those who accompany Ministers on engagements use the mobile device to capture moments and post them in real time. In Aotearoa/New Zealand we operate under an electoral system that produces multi-party governments, things are globalised, policy challenges are wicked and messy, and it's 24/7.

It would be fanciful to suggest that these kinds of changes would not result in corresponding changes in roles and functions within executive government. And they have. But the constitutional principles, conventions, and expectations underpinning them have remained largely constant. Enter free and frank advice.

Constitutional obligations

When it comes to the obligations of the public service in a Westminster system these are of a constitutional kind. Providing a Minister with free and frank advice is not simply a sensible thing to do, it is a constitutional obligation, and it is an obligation that rests both on those giving it and those receiving it.

Ministers may not choose not to receive that advice, although they may choose not to act on it. Political advisers who in any manner frustrate the discharge of this obligation or modify advice act against the Constitution.

That perhaps is one of the reasons why Sir Geoffrey Palmer and Andrew Butler want to include a section on the role, duties and obligations of public servants in a Constitution for Aotearoa/New Zealand. We should note in passing that the provision that they have drafted would have the NZ Parliament possessing the final say on the appointment of the State Services Commissioner.

Political advisers can and do add value – our respondents told us that in 2005, and we heard the same thing in 2017. But they also told us that political advisers compromise the capacity of the public service to tender that advice, that they filter, and they frustrate. Not all of them, and not all of the time, but it is a risk and it has grown over time.

On occasions it has constituted extreme politicisation and abuse of process – excursions into the political equivalent of 'black ops'. There are books on this, and they simply cannot be dismissed as 'leftist' conspiracies.

When we conducted our 2005 research, 188 public servants responded. Of the 640 individuals who accepted our invitation to participate in the 2017 research 417 are presently employed in the public service.

As can be seen from the data in the tables above, there is a significant measure of concern on the part of public servants over the influence that political advisers may have or are having on the capacity of the public service to discharge its responsibilities – constitutional responsibilities to the government of the day.

Respondents voice concerns

Moreover, we invited our respondents to provide written comments. Here are the voices of two of our respondents.

- "Ministers are welcome to have political advisers who play a minor role in ‘separately’ providing politically oriented advice. The problem is when they act as an intermediary between the Minister and public servants, who are trying to provide free, frank and politically neutral policy advice. They frequently filter what policy advice goes to the Minister, actively argue against policy advice in officials' meetings and work hard to influence the topics and content of advice. Those behaviours would be less problematic if ministries' senior management fought to uphold the Westminster model of neutral policy advice - but these days, they seem to understand their role as providing politically oriented advice to implement the already-chosen policies of the Government of the day. This means they seek the approval of political advisers, seek their input, etc. in order to please the Minister."

- "They do interfere with the provision of free and frank advice, they overstep their boundaries, trying to tell government departments which options are or are not acceptable before a paper is submitted to Ministers or Cabinet. They can interfere with the ability for officials to meet with Ministers, and sway the Minister's views before the Minister has received advice from government departments. Political neutrality of the public service is at risk."

Where to from here?

First there needs to be acceptance that there is a problem, or at the very least a willingness to engage in a conversation that admits that all is not well.

It was refreshing to hear the Chief Ombudsman, Judge Peter Boshier, in a recent radio interview engaging with issues like the influence of political staff, politicisation, the challenges to free and frank advice, and on how to ensure transparency in an environment where senior officials and Ministers are risk averse and where 'no surprises' is not just a consideration, but the zeitgeist of the times.

Second, at some point in time (clearly they are busy) we need to know what the new Government’s views are on the matters that the Chief Ombudsman traversed in his interview. Is it going to be 'business as usual' and an endorsement of the 'official Wellington bureaucratic narrative', or are we going to see some long overdue changes?

Many of our respondents would like to know. We would like to know. And the citizens of Aotearoa/New Zealand deserve to know.

- Link to full research results

- Download paper to the New Zealand Political Studies Association Conference

This article was originally published on the Newsroom website.