Publication success for bilingual poet and translator

Liang Yujing, a PhD student with the School of Languages and Cultures, has been widely published in journals and magazines the world over, but this year has also welcomed his first book of solo translation from Chinese to English.

Publication success for bilingual poet and translator

Liang Yujing, a PhD student with the School of Languages and Cultures, has been widely published in journals and magazines the world over, but this year has also welcomed his first book of solo translation from Chinese to English.

A Q&A with Liang Yujing

Why did you start translating poetry and what keeps you doing it?

I started translating poetry from English into Chinese when I was an undergraduate in Wuhan, China. I was then majoring in English and I wrote poetry myself in Chinese. When I studied the English poets like Shakespeare and Shelley, I would translate them into Chinese. Though my translation may not have been so good back then, it was good practice and an accumulation of experience.

In 2005, I met the Chinese-Australian poet and translator Ouyang Yu, who taught us creative writing and encouraged me to write poetry in English—in his words, the ‘father tongue’. He organised an English poetry contest in class and I won the first prize, which was my first step towards writing in English.

I started writing poetry in English and submitted them to magazines in the US, UK and Australia—some of them got published. In 2011, I began to know some Chinese poets, mostly young poets. Since I could write poetry in English, I thought I might try to translate their work into English. My translations were soon accepted by a number of magazines—Modern Poetry in Translation, Boston Review, The Poetry Review, Westerly, Poetry NZ, to name a few.

In retrospect, there are four clear stages in my writing and translation career—writing poetry in Chinese, translating poetry from English into Chinese, then writing poetry in English, then translating poetry from Chinese into English. I gradually went from Chinese to English, from writing to translation. The unchanging keyword is poetry. There is always something new awaiting me to try. I think that’s the major reason I keep doing such work.

What has been the most surprising discovery from your research journey so far?

My PhD research does not include a translation project but focuses on the word minjian in contemporary Chinese poetry. Minjian, which literary means ‘among the people’ has multi-layered meanings in the context of contemporary Chinese poetry. It stands for down-to-earth poetics, an unofficial stance and an affiliation with similar elements in English poetry, such as Charles Bukowski. This part of Chinese poetry is a relatively new field in English scholarship as most scholars still focus on the Misty poets, the previous generation of Chinese poets. In my research, I also have to translate some poems into English from time to time, so my translation skills also help.

What is the creative process of translation for you?

I think the process of translation is not just the translation itself, but involves three questions: What work you translate? How you translate? Where you publish your translations? Translation is effective only when the three questions find their correct answers. For me, I would translate a poem as long as I think it is good, regardless of the author’s reputation. And I tend to translate the young and unknown poets rather than the ‘famous’ ones. Good poems are hidden gems—you have to dig them out. Also, a good translator should know where to publish his work to get a wider audience in the target language. A translation makes no sense if it can’t reach its target readers.

As for the creative process of translation, I disagree with Robert Frost’s ‘poetry is what gets lost in translation’. This statement presumes the secondary status of translation—it is not as good as the original because something ‘gets lost’. However, it fails to admit something can also be gained or regained in translation, as long as the translator is creative enough to write a new poem in another language. Translating is writing and vice versa. Due to the difference between the two languages, something new can be generated through translation, even something lacking in the original. And sometimes this acquisition is unexpected, a surprise. The following poem by Shen Haobo can be an illustration. In my English translation, the lines beginning with ‘A’ give the poem a different structure, not existing in the original, as the Chinese language does not have such articles as ‘A’.

花莲之夜

寂静的

海风吹拂的夜晚

宽阔

无人的马路

一只蜗牛

缓慢的爬行

一辆摩托车开来

在它的呼啸中

仍能听到

嘎嘣

一声

Night of Hualien

A silent

night with sea breezes.

A broad,

empty highway.

A snail

crawls slowly.

A motorbike passes.

In its whizz

you can still hear

a

crack.

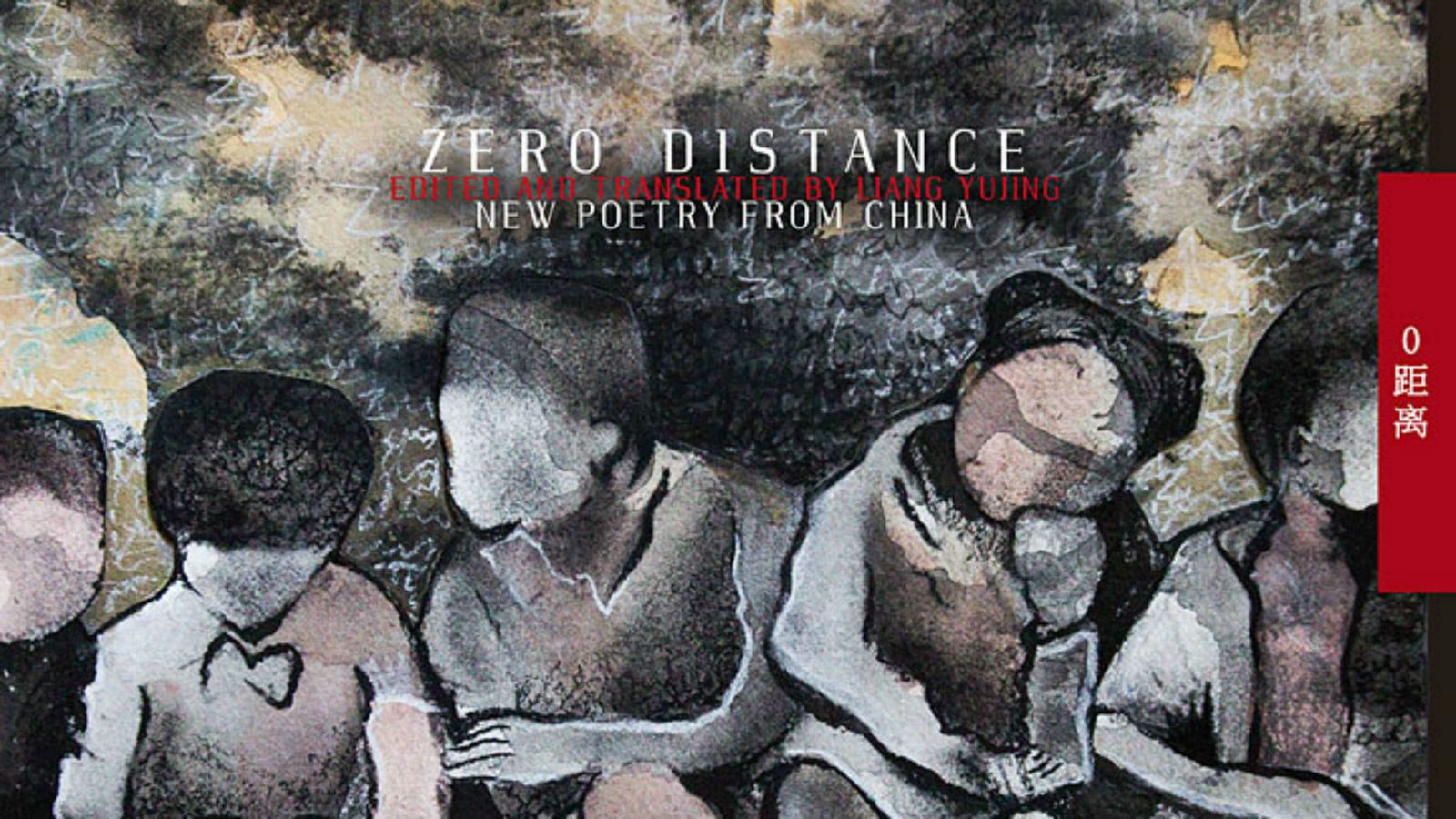

Zero Distance: New Poetry from China is the first publication by Liang Yujing, featuring poetry from mostly unknown Chinese poets, translated into English.

Zero Distance can be purchased online from Tin Fish Press or Small Press Distribution.

Contact:

Phone:

Email: