Ruth—a research services librarian at the University—scoured the pages of New Zealand parliamentary debates from 1890 to 1950 to study unparliamentary language for her PhD in Applied Linguistics in 2016. Since then, she has continued to study the colourful but rarely explored area in New Zealand and, in recently published research, she has honed in to identify the parliamentarians most likely to get called ‘out of order’ for their language.

Early offenders from the 1890s were a group she categorises as “mavericks, loners and bullies”—often Members of Parliament pushing a single issue such as prohibition, or those on the margins of a political party. An example is MP Frederick Pirani—at different times a Liberal, Conservative, and independent MP—who responded to a comment about his wife breaking an umbrella over his head in a public place by accusing Premier Richard Seddon of ‘slander’. Pirani refused to withdraw the comment and was suspended from Parliament for a day.

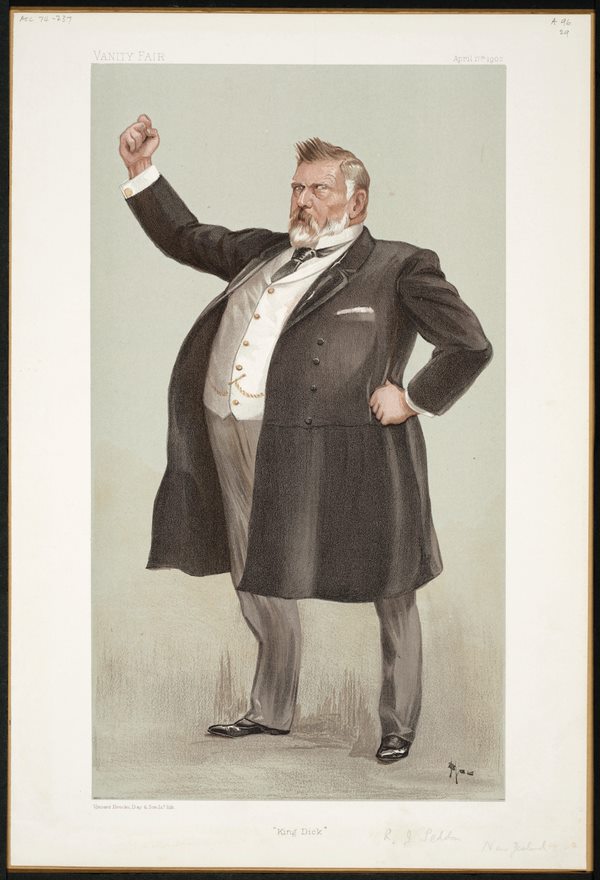

Ruth says Seddon himself was a serial transgressor, using unparliamentary language to target opponents and warning others not to challenge him. “He was expert at saying something quite outrageous about a person and then withdrawing and apologising and, when he died in 1906, occurrences of unparliamentary language plummeted for a time.”

Among others to employ strategic insults were a small group of socialist MPs who entered Parliament from about 1906. “People like miners, Australians, often quite rough, who wanted to strongly push their philosophy.”

One of them, John Payne, was suspended from Parliament for phrases such as “you miserable dodger” and “you are becoming a professional crawler”, while Australian-born Alfred Hindmarsh—the first leader of the New Zealand Labour party—was rebuked several times for using the term “cur”, meaning mongrel dog.

Insults involving animal and bird metaphors were a regular occurrence and it’s an area Ruth would like to explore further.

“I identified over 100 in the first part of the research—all sorts of animal names people called each other, like ‘dirty dingo’, ‘political magpies’—dogs feature a lot, also birds and rats.”

Then there is the more elegant phrase, “a transparent piece of insincerity”, which earned New Zealand’s first woman MP, Elizabeth McCombs, a rebuke.

In the 1930s, three Labour MPs were the main perpetrators, particularly Bob Semple who asked of the United–Reform Government, “how can decent men listen to such cant, humbug, hypocrite, and somersaulting?” Ruth says the unstable political situation, set against the background of the Great Depression, led the MPs to step up the use of unparliamentary language to challenge the Government.

Ruth juggles her ongoing research with her library work, often writing at the weekends. She says that continuing her research is helpful to her day job. “I work with a team that supports academics and our early researchers in their journey, so the fact I can relate to the things they are saying is really invaluable—such as to guide them to publish with the good journals and to stick with it.”