Dr Lee Davidson is a Senior Lecturer in the Museum and Heritage Studies Programme of Victoria University of Wellington’s Stout Research Centre for New Zealand Studies. For the past few years, she has been researching international touring exhibitions. She views these as a form of ‘cultural diplomacy’ between museums and nations, acting as sites of intercultural understanding and exchange.

International touring exhibitions are a well-established part of the global museum landscape. Museums develop an exhibition, then loan the objects and related materials to other institutions around the world. The museums and nations that develop and receive these exhibitions see benefits for audience expansion, tourism and diplomacy. However, there has been little research into how collaboration between museums is managed and what these exhibitions actually accomplish.

Dr Davidson’s research began in 2011, in collaboration with a Mexican colleague, Professor Leticia Pérez Castellanos. They were interested in museums and exhibitions as “cultural products that are implicated in wider diplomatic contexts” involving museum professionals, heritage institutions, nations and audiences of differing cultural backgrounds.

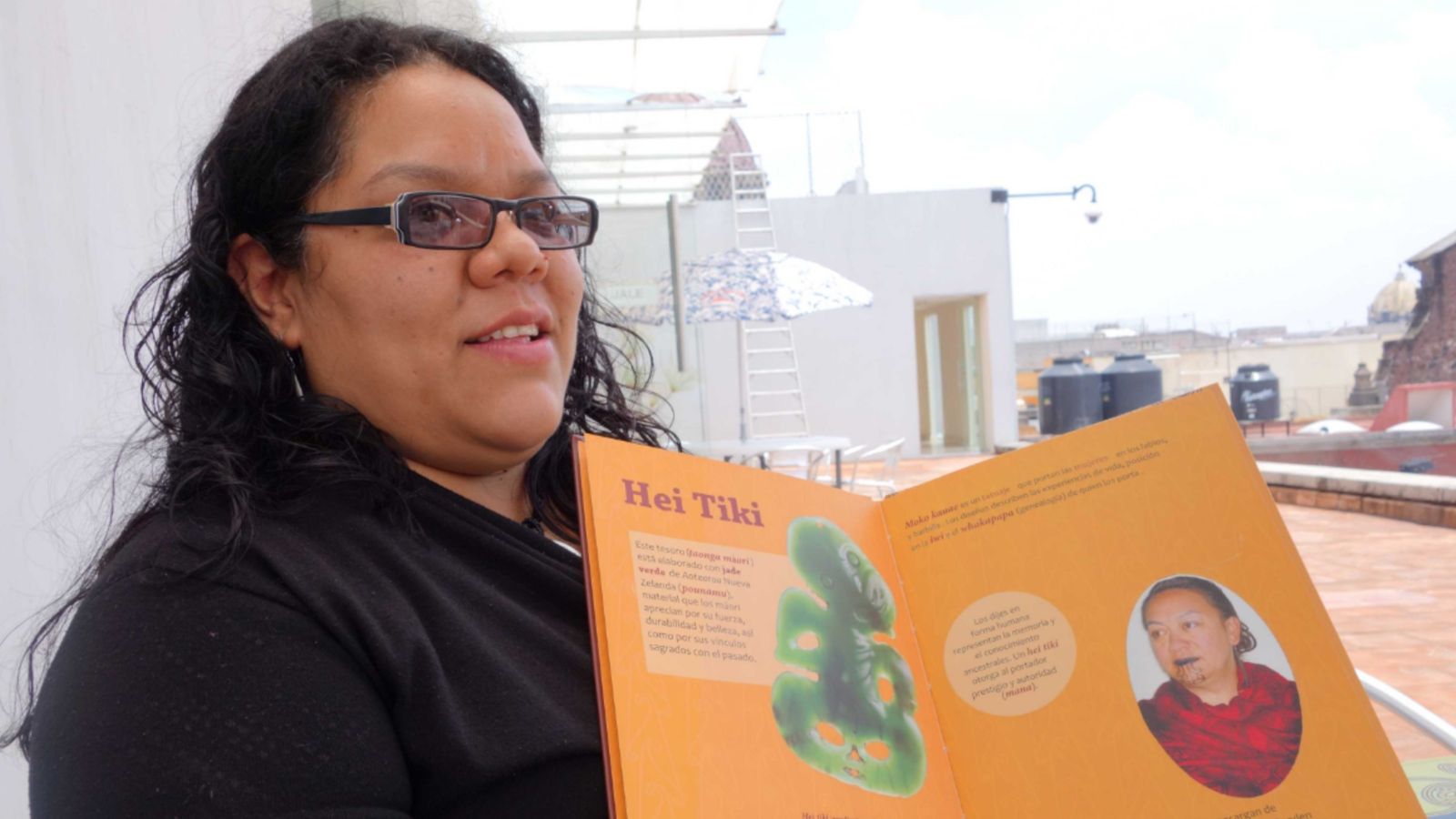

Together, Dr Davidson and Professor Castellanos took two exhibitions as case studies. The first, curated by staff at Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand, was E Tū Ake, an exploration of living Māori culture in the past and present. It was displayed at Te Papa, before touring Paris, Mexico City and Quebec City between 2011 and 2013. The second, Aztecs: Conquest and Glory, told the story of the Aztec Empire up to the period of Spanish conquest. Developed by Te Papa and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia in Mexico, it toured New Zealand and Australia between 2013 and 2015.

Dr Davidson and Professor Castellanos conducted interviews with the museum professionals who worked on these exhibitions. They wanted to understand how staff worked through cultural and institutional differences when working with their colleagues in other museums.

From the issues and solutions identified in these interviews, they developed recommendations for curatorial practice and positive collaboration when creating international exhibitions. They recently published Cosmopolitan Ambassadors: International Exhibitions, Cultural Diplomacy and the Polycentral Museum (Vernon Press, 2019) detailing these findings.

Dr Davidson and Professor Castellanos also communicated their findings through a series of workshops in New Zealand in July and August. Thanks to a grant from the group that oversees Victoria University of Wellington’s ‘Enriching national culture’ area of academic distinctiveness, Professor Castellanos was able to join Dr Davidson for the workshops. They worked with current and emerging museum professionals, discussing how their findings can translate into guidelines for developing international exhibitions.

Dr Davidson sees these guidelines as having implications for domestic practice as well as international. The same lessons for productive cross-cultural collaboration are useful for museums working with local communities of different cultural backgrounds.

She and Professor Castellanos also spoke with members of the public in New Zealand, Australia and Mexico who visited E Tū Ake and Aztecs. If international exhibitions seek to foster intercultural understanding, what is it that visitors relate to and take away with them? How is this affected by the different personal or cultural experiences each visitor brings?

Dr Davidson was impressed by the range of responses her interviewees provided. “People relate to exhibitions very emotionally, not just cognitively. Sure, people want to go along and see amazing objects and learn about amazing cultures, but also they want to relate what they see there to their own lives.”

She believes these kinds of exhibitions are important in an increasingly globalised world. “They help people in different cultures get to understand each other. They can help us develop better these inter-cultural skills.” There is a tendency among some museums to see international touring exhibitions solely as blockbusters that bring in revenue and new audiences. But there is a “missed opportunity” if museums ignore the potential to promote intercultural understanding.

Dr Davidson intends to build on the successes of the project so far. Her research will continue to explore how these kinds of exhibitions occur and what makes them important for museums, countries and the people who visit them.